By Jude Dry

‘The Last Resort’ Review: Miami’s Post-WWII Jewish Population Shines in Spirited Documentary

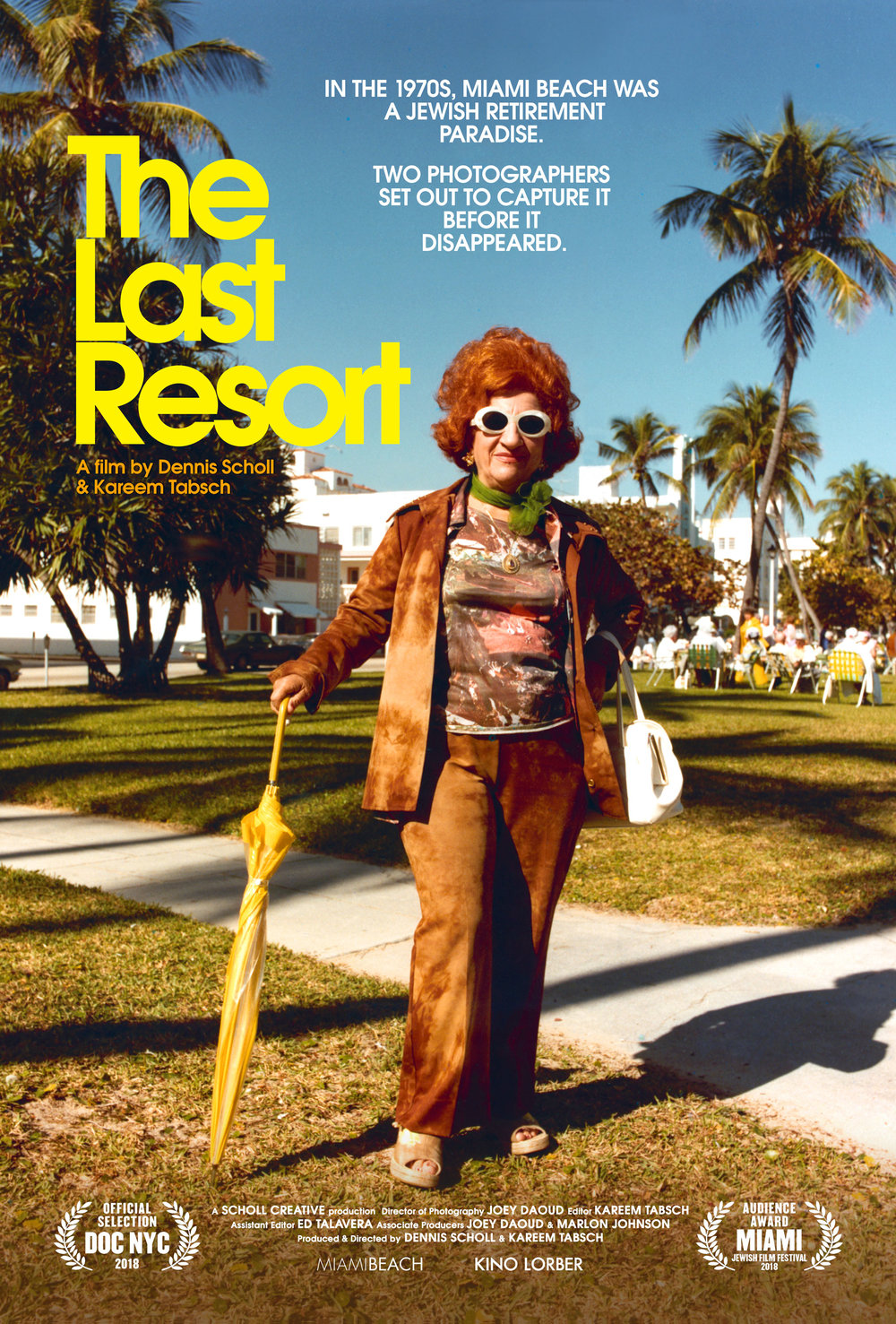

Part mystery, part anthropological study, a new film illuminates the lost legacy of a queer photographer in stunning technicolor.

If any of the subjects of Andy Sweet’s colorful photographs were alive today, they might wonder: “Whatever happened to that nice boy? He was such a mensch.” They would certainly be saddened to learn of his grisly death, but heartened to see his remarkable work recognized in Kareem Tabsch and Dennis Scholl’s delightful love letter to Miami’s South Beach, the charming new documentary “The Last Resort.”

Using Sweet’s vibrant photography as a framing device and visual palette, this charming documentary — like Miami itself — has a little bit of everything: Old Jews, Art Deco architecture, serious beach style, rival artists, and a dash of queerness for good measure. Just don’t expect funny one-liners from nonagenarian caricatures; “The Last Resort” is more photographic history lesson than comic character study. The film benefits from plenty of truth-is-stranger-than-fiction twists, and the result is a patchwork storytelling technique that leaves the film lacking a singular focus. While that may have been the best way to present a surplus of great material, it makes the movie difficult to summarize in a single logline.

In 1977, two young friends embarked on what became the Miami Beach Project, vowing to photograph Miami Beach’s Jewish retirees every day for ten years. Andy Sweet and Gary Monroe had vastly different styles; Sweet eschewed formalist composition techniques for a more improvisational, spontaneous framing, while Monroe’s black-and-white compositions are far more somber but equally arresting. Long before the term “street photography” was ushered into ubiquity by a fashion-hungry internet, Sweet was snapping his shutter with wild abandon, finding humanity in the split-seconds and spaces in between.

The Miami Beach Project was an attempt to capture the last days of a dying breed, the Jewish retirees who settled South Beach in the wake of WWII. What began in the 1950s as a winter vacation spot for Holocaust survivors to relax in the sunshine eventually became a vibrant retirement community throughout the 1970s and early ’80s. Using Sweet’s exceptional illustrations, “The Last Resort” invites viewers to imagine a Miami Beach as bustling as it is today, replacing scantily-clad youth with, well, scantily-clad senior citizens.

In talking head interviews, Monroe provides insight into Sweet’s artistic philosophy and unique (certainly at the time) playful spontaneity. A Miami native and admirer of Sweet’s work, “Certain Women” filmmaker Kelly Reichardt helps place him in the context of his would-be contemporaries. Halfway through the Miami Beach Project in 1982, Sweet died tragically, murdered in a botched drug deal at the age of 28. The gruesome nature of his death and subsequent trial caused a media frenzy that captivated the city and eclipsed his work, which had only recently started gaining attention.

Sweet’s work is a time capsule of a bygone era, preserved in glorious, saturated technicolor. He was the master of the unexpected composition, and in that sense, “The Last Resort” is a fitting tribute. Tabsch and Scholl assemble the fragments of his far-reaching story as best they can, but run into trouble when skirting the delicate line between glorifying Miami’s Jewish past without bemoaning its Cuban present. By the end of the 1980s, the Mahjong clubs and porch sitters were replaced by drug dealers and violent crime. A throwaway explanation about Fidel Castro emptying Cuba’s jails onto Miami Beach comes off as overly simplistic scapegoating.

The shifting demographics of neighborhoods is a far more fraught topic today than it was in Sweet’s time, and it’s tricky to romanticize the disappearance of one group without implicitly blaming whatever replaced it. Nostalgia, like a wide-eyed young photographer, has its own visual tricks; it casts a warm glow on whatever it touches. One thing is for certain, we could all stand to see the world the way Andy Sweet did.