Alina Cohen

Photographs That Captured 1970s Miami as a Paradise for Jewish Retirees

Floral patterns, shades of fuschia and pear, and bold Art Deco structures enliven Andy Sweet’s pictures of 1970s South Beach, Miami.

Even the photographer’s last name suggests the merriment and candy hues that color his frames. Though Sweet sometimes turned his lens on young beachgoers and drag queens at the Eden Roc hotel, he mostly focused on his hometown’s Jewish retirement community. In his photographs, elderly residents radiate youthfulness, tanning by the ocean, gossiping by the pool, and lounging under sausage-shaped balloons on New Year’s Eve. Beneath this levity, however, lies a darker tale.

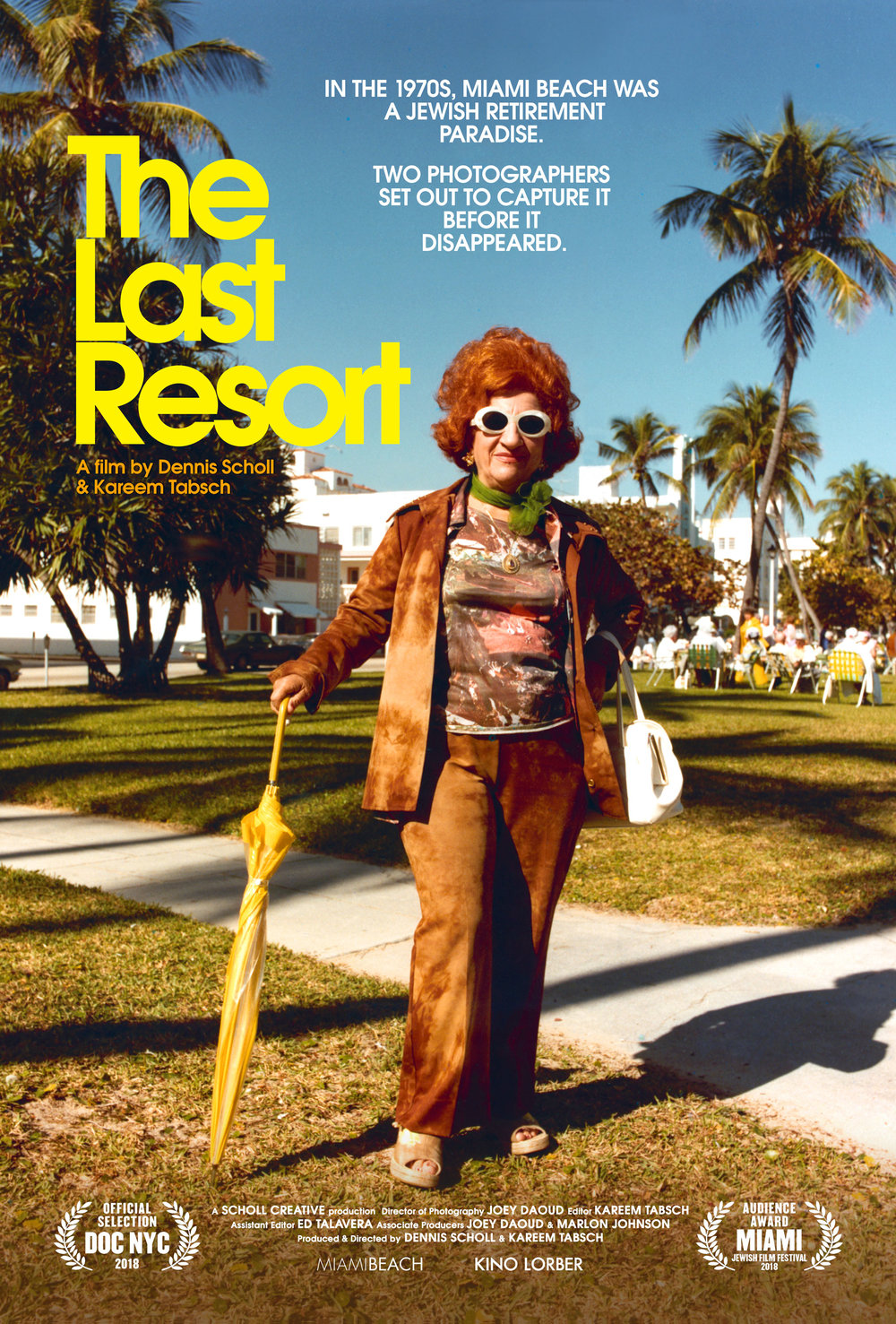

This past December, Miami-based filmmakers Dennis Scholl and Kareem Tabsch released a new documentary, The Last Resort, that explores the surprising and tragic intersections between Sweet’s work and the history of Miami Beach. (The film, following its New York release, will screen in Florida in February, in Los Angeles in March, and on Netflix in April.) When they began the project two years ago, they merely set out to make a film about Sweet and his friend Gary Monroe, who also photographed Miami’s aging community in the 1970s. “The great thing about a documentary film, unlike a narrative feature, is that it tells you what it wants to be,” Scholl explained recently over the phone. The more time they spent looking at the photographs of Sweet and Monroe and speaking to people knowledgeable about Miami’s history, the more the film became a tale of a community at one moment in time, both vibrant and unsustainable.

Miami Beach remained undeveloped until around the 1940s, following the end of World War II. Developers built fancy hotels, such as the Fontainebleau, where guests could see Liberace or Frank Sinatra perform at night. Throughout the 1960s and early ’70s, as the rest of the country experienced political unrest, Miami Beach remained a sunny, quiet haven. Throughout the 1970s, New Yorkers—many of them Jewish, often retirees—headed south. In archival footage shown in The Last Resort, a woman in a wide-brimmed hat offers her rationale: “In New York, all you do is just think of your death,” she says, in a thick tri-state accent. “Tomorrow I’m gonna die, and I’m just sitting, waiting.” In Miami, the elderly could relax in the sun. A culture of “porch sitting”—seniors sitting on patios—emerged.

Monroe and Sweet, who were both born in the 1950s, grew up in that tranquil environment, surrounded by a strong Jewish community. After they graduated from the MFA program at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in 1977, they moved back home to Miami and agreed to photograph their city and its quirky inhabitants every day for 10 years. Many of their subsequent pictures feature porch-sitters and subjects lounging in deck chairs—a sense of communal ease prevails. “We saw something that I later realized was a precious legacy that was being forgotten, that was vanishing,” Monroe says in the film. Though the senior citizens were vivacious, they were also approaching death.

Despite their shared subject matter, Monroe and Sweet distinguished themselves with their divergent styles. Monroe was concerned with form and composition, and his black-and-white pictures are somber, even when the content is not. Sixth Street—South Beach, Florida (1978), for example, features three women and a man walking along a sidewalk. Two of them wheel carts, while one holds an umbrella above her head to shield herself from the sun. The camera seems more interested in symmetry and the contrast of light and shadow than in the individuals themselves.

On the other hand, Sweet’s more casual images prioritized character, like in his portrait of an elderly woman with curly, orange hair wearing a “Happy New Year” headband. (The pair visited multiple hotels on New Year’s Eve, catching their elderly subjects celebrating the passage of time.) Yellow and red leis crisscross the woman’s shoulders, and she holds a half-full plastic cup in her hand, her festive get-up belying her tired expression: She’s partied too much for one night. Illuminated by Sweet’s flash in a darkened room, she appears nearly angelic. These contrasts contribute to the gentle humor that infuses the photograph, and much of Sweet’s oeuvre.

Yet as the 1970s ended, time eroded Miami Beach in new ways. The retiree population was dwindling as they passed away, and the hotels were decaying. In 1980, Fidel Castro launched the Mariel Boatlift, which allowed Cuban citizens to leave the country at the Mariel port near Havana. Miami welcomed about 125,000 refugees, and while the immigrant population mostly enlivened Miami’s culture, Castro released criminals from jail to make the journey, as well; the dictator’s sabotage introduced murderers and thieves into the city. Colombian drug lords also infiltrated Miami, amplifying the cocaine trade and catalyzing the drug wars. The city’s unrest was amplified in 1980, when riots ensued following the acquittal of four white police officers who had killed a black motorist, Arthur McDuffie, then lied about how he had died.

Sweet himself fell victim to the city’s emerging violence. In the film, his sister, Ellen, asserts that he had a drug problem. Monroe recalls that Sweet was hanging around “seedy” people, sleeping later, and photographing less. In October 1982, when Sweet was 28 years old, Monroe found him dead at home. His assailants had stabbed him 27 times, for reasons that still remain unclear.

Sweet’s family moved his work into an art-storage facility, but they lost five boxes of his archives. Meanwhile, the city was changing again: New York developers were renovating the old Art Deco buildings and raising rents. Sweet, unfortunately, wasn’t around to capture these shifts.

Years later, Ellen’s partner, Stan Hughes, found Sweet’s old contact sheets. Using digital photography, he colorized the old, faded prints. Once again, Sweet’s teal pools glistened in the sun, while purple bathing suits shone.

Tabsch described his documentary as “a relationship film.” He explained: “It’s a relationship between these two artists, between them and the community they’re photographing, between the viewers and the community.” He noted that many people come up to him after viewing the film to discuss their own ancestors who once lived on South Beach; some audience members even recognize their grandparents, or great-grandparents, in Sweet’s pictures. In addition to immortalizing the velour tracksuits, leopard-print sofas, and jubilant, dancing couples of the era, the photographer also preserved a fading lifestyle. His pictures, tinged with the warm nostalgia of 1970s Miami, lead viewers to contemplate their own family histories, wherever their nanas ended up.