By Theo Yurevitch

Old Miami stays alive in ‘The Last Resort’

What comes to mind when you think of Miami? Night clubs and beaches? White suits and bikinis? Maybe Cuban sandwiches? What about elderly Jewish retirees? In mid-20th century South Beach, that’s what there mostly was.

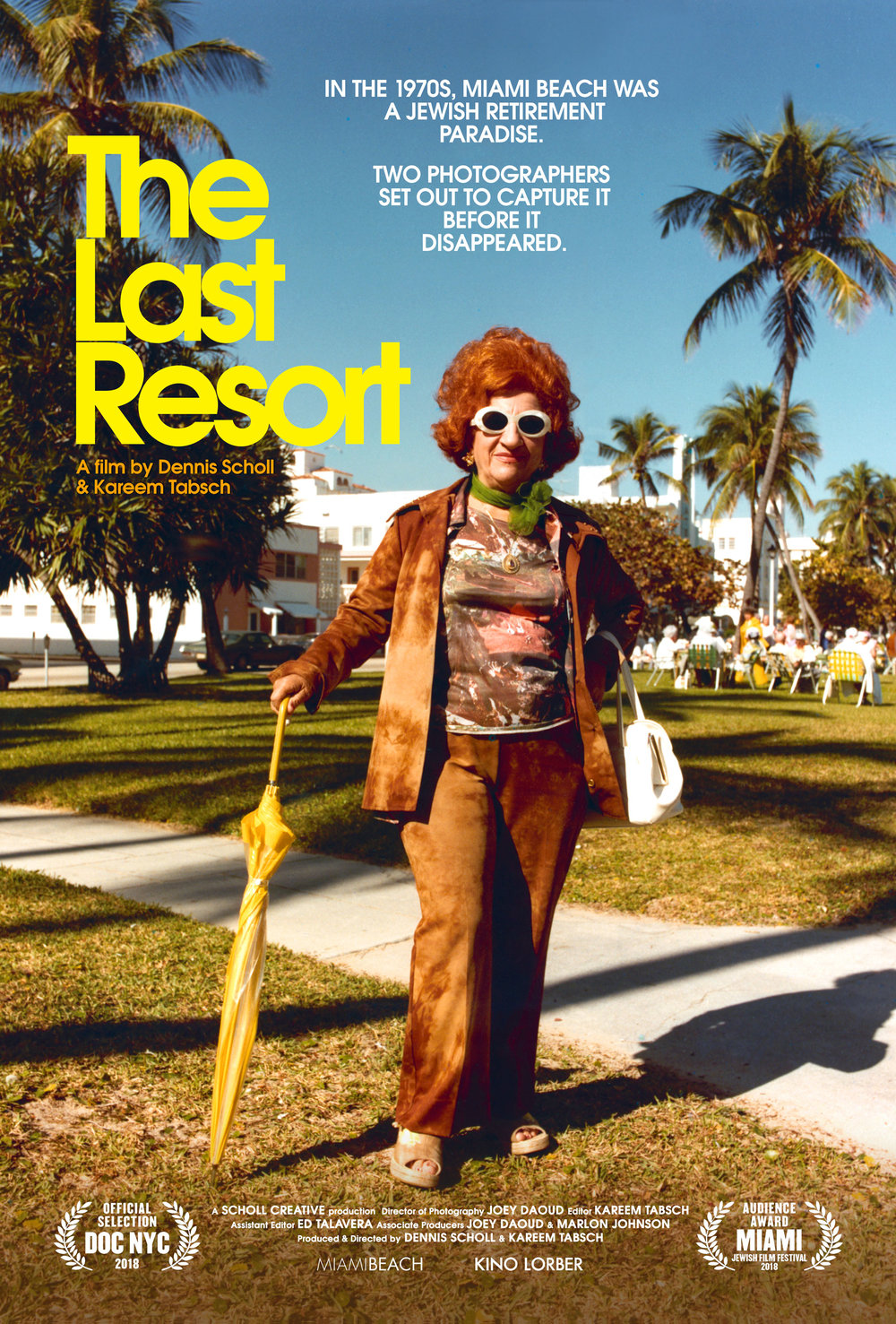

And in Dennis Scholl and Kareem Tabsch’s latest documentary, “The Last Resort,” they depict the era lovingly.

The film is a collage of sorts, a collection of home video, photography, and interviews with notable Miamians like the critically acclaimed filmmaker Kelly Reichardt and the photographer Gary Monroe.

While the film’s attention sometimes slides all over the place, Scholl and Tabsch eventually settle on providing a historical overview from Miami’s incorporation in 1896 up to the post-WWII era when Jewish New Yorkers flocked to South Beach.

They came for warm breezes and cheap rents in the hotels that lined the shore, but the resort area was more than just a beautiful place for them to live. For many, it was literally their last resort after centuries of persecution and discrimination.

By the ’70s, South Beach “was like a shtetl,” as one interviewee would describe it, with the most visible demographic being octogenarians.

But there was at least one young man amid all these older folks — Andy Sweet — and it’s with him the film really finds its heart. It was 1977 and Sweet was in his mid-20s when he decided to embark on a decade long project photographing the fading community in South Beach.

“The Last Resort” uses his vibrant photographs wisely, letting them tell dozens of stories even when the other elements of the documentary lose focus. They’re beautiful photographs, after all; full of vibrant colors, and not just because of the glittering beaches and pastel architecture in the background.

Sweet’s subject is people, often candid — and usually wrinkly — but always full of life, whether that be while swimming, lounging on a porch, or laughing with friends. “The Last Resort’s” steady stream of his stellar work is worth the price of admission alone.

The sun sets eventually, though, and the documentary does veer into the changes that occurred in South Beach throughout the ’80s. The gentrification of the area is touched on, but Scholl and Tabsch point the story toward the more sensational developments, like the rise of crime and drugs in the area.

The last act narrows haphazardly into an examination of Andy Sweet’s life and how he never finished his decade long project. His is a compelling story, but the movie makes some egregious mistakes lumping his sexual orientation into his alleged drug use.

Nevertheless, there’s a lot of charming, if disparate, parts to “The Last Resort.” For anyone with ties to South Beach and the thriving community that lived there until they were driven out by real estate developers, this is a must-see. Same goes for photography enthusiasts — it’s a small miracle Sweet’s work survives at all, and that is a story the film does deliver well.

“The Last Resort” might not always be the smoothest experience, but it’s full of heart and nostalgia — and some killer smooth radio hits in the soundtrack, too.