By Andrew Travers

Meet Aspenite and Accidental Auteur Dennis Scholl

The documentarian followed an unexpected path into filmmaking and found that he loves life behind the lens.

In Dennis Scholl’s sweeping multi-hyphenate career, he has been a finance lawyer and a venture capitalist, a renowned art collector and an influential philanthropist, an award-winning maker of wines and, of late, films.

At 60, Scholl is as surprised as anyone to find himself behind the camera. “I have a long career as a patron and as a facilitator,” he says. “But I never had the courage to be a maker.”

Scholl’s foray into filmmaking traces back to his stint as a culture correspondent for the now-defunct Plum TV, beginning in 2008, where he reported stories for the network from Aspen and Miami (he and his wife, Debra, split their time between the two). At the Miami station, Scholl met filmmaker Marlon Johnson, and the two decided to co-direct a documentary. Their first effort was Sunday’s Best—a six-minute piece about women’s church hats inspired by the crystal-ringed wool chapeau that Aretha Franklin wore at Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration.

Making the film was a creative lark. But when it earned a spot at Aspen Shortsfest in 2010 and garnered some festival buzz, Scholl thought he might be on to something. “I don’t think I would have kept going had I not gotten so much encouragement from the Aspen Shortsfest folks,” he says now.

Sunday’s Best later won a Regional Emmy Award—the first of nine now on Scholl’s mantel—and broke open the cinematic floodgates for this polymath. Scholl has now produced and/or directed 20 films in the past seven years, many of which have been shown at festivals like Sundance and SXSW, and on PBS.

Broadly speaking, those movies—most running 30 minutes to an hour—consider artists and their social impact. Subjects have ranged from artist and urban planner Theaster Gates to Cuban ballerina Rosario “Charin” Suárez to the history of soul music in south Florida.

Scholl’s films are well-served by his immaculate taste and keen eye for the next big thing—the same attributes that helped make him and Debra some of the world’s most prominent art collectors. (Their 500-piece collection of contemporary aboriginal Australian works, believed to be the world’s largest, is currently on a tour of US museums.) Likewise, those attributes helped ensure success for the Betts & Scholl brand of wines; he and partner Richard Betts sold the label in 2009, but Scholl will launch a boutique Shiraz, called Mother’s Tongue, later this year.

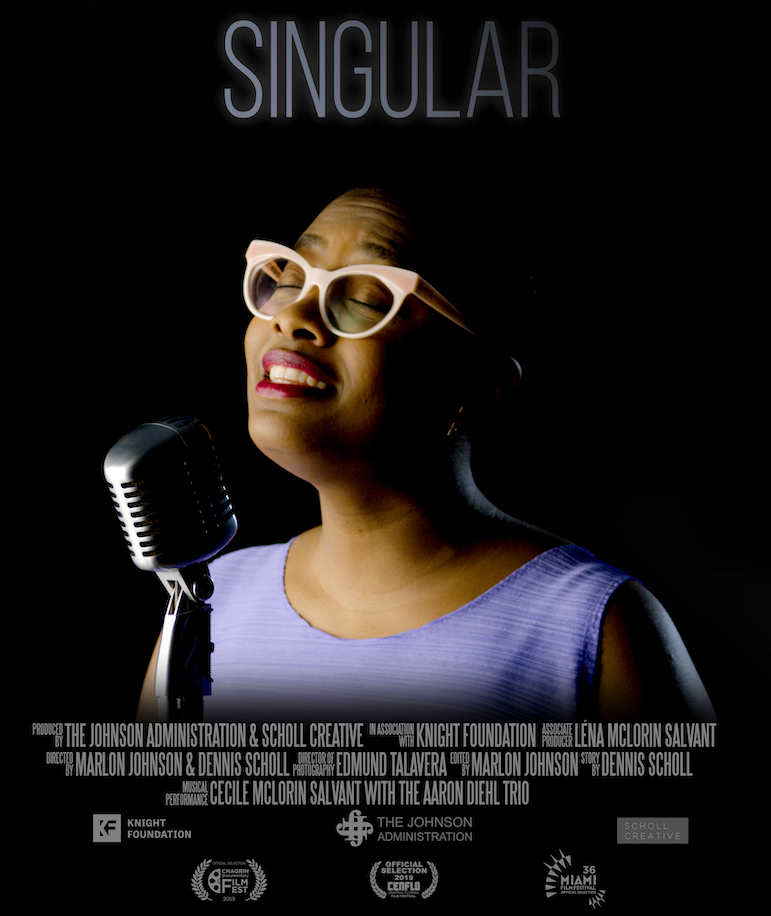

This spring two new Scholl titles will hit the festival circuit. Symphony in D is about a crowd-sourced work performed by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and overseen by MIT composer Tod Machover. The other, tentatively titled Woman Child, portrays ascendant 27-year-old jazz singer Cécile McLorin Salvant, in the wake of the Haitian-American phenom’s 2013 debut album. The projects saw Scholl and his crew hopping among Detroit, Haiti, New York, Cambridge, Miami, and Europe.

Later this year, Scholl aims to release a third film, on abstract expressionist painter Clyfford Still, whose once-neglected place in art history has been restored since the 2011 opening of the Still Museum in Denver. Scholl taped interviews with the likes of Roni Horn, Julian Schnabel, and Jerry Saltz to assess Still’s legacy. “We’re trying to give a contemporary bent to the story,” he says. “I’m excited about it. It’s certainly the biggest film we’ve ever made.”

As if that’s not enough, two additional documentaries are currently in production. The flurry of films on the way, Scholl says, resulted from his enthusiasm for full-time filmmaking after he stepped down from his post running the Knight Foundation’s arts program in 2015. “I wound up taking on a bunch of projects at once, because I was afraid no one would ask me to do anything ever again,” he chuckles. “Now I have to do them.”

Scholl largely self-funds his films, which he makes purely with the hopes of sharing a good story with the widest possible audience. PBS has proved to be a regular outlet for reaching those viewers. Everyone Has a Place, his and Johnson’s documentary about Wynton Marsalis’s original composition Abyssinian Mass, landed on PBS affiliates covering 80 percent of the US, while both Symphony in D and the Salvant doc are slated for PBS broadcasts in the fall.

Untethered by concerns for making money or selling to distributors, Scholl has immense creative freedom, a luxury he acknowledges. “I have the good fortune of being able to pick my projects,” he says. While “filmmaker” is Scholl’s latest title, and his main gig for the foreseeable future, don’t expect it to be his last. After all, a true renaissance man never quits.