By Paul Parcellin

The Last Resort

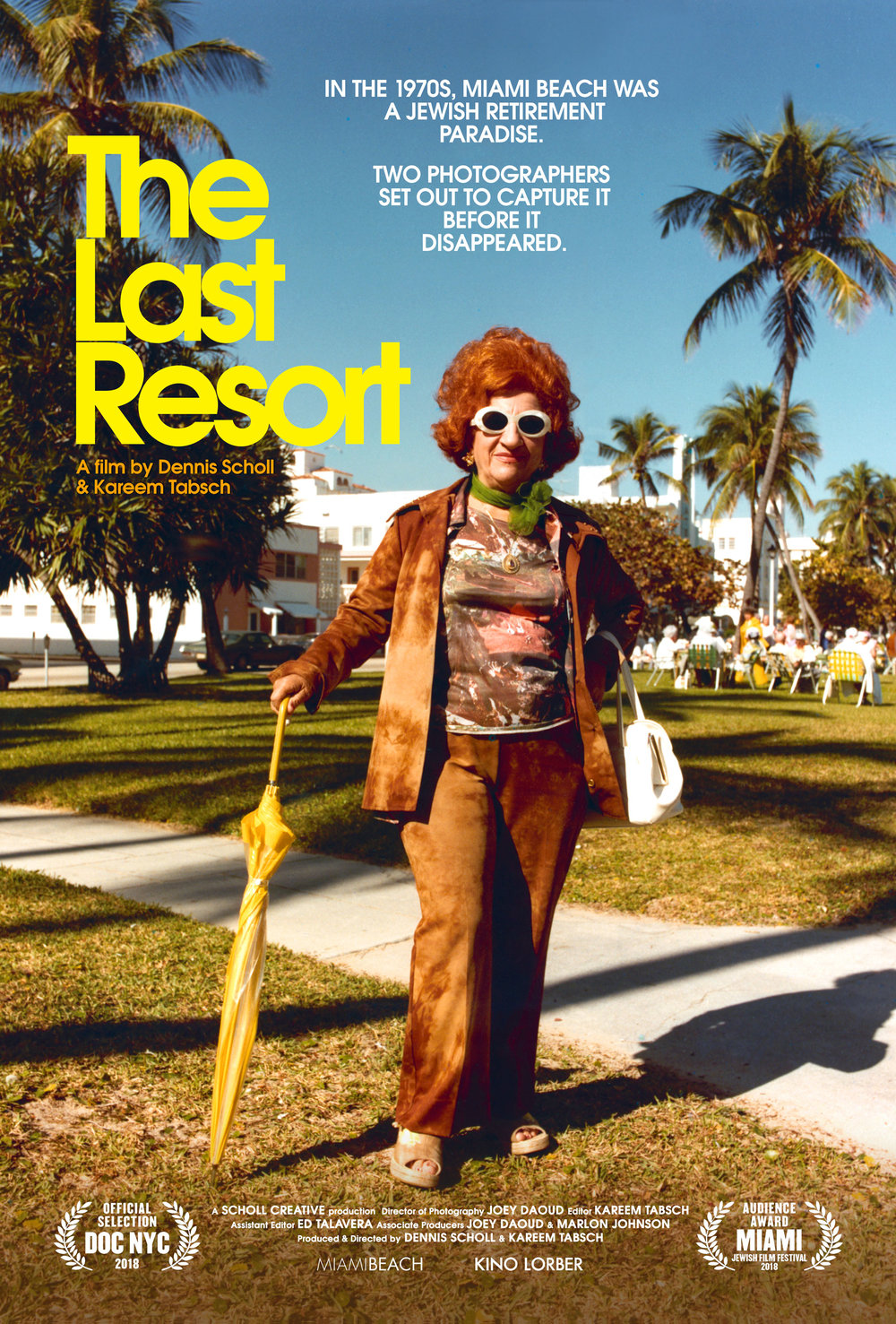

The Last Resort could have been a slight, sunny picture postcard from Biscayne Bay. A piece of fluff that would delight our cravings for the past — whether or not we were actually around to observe that not too distant past firsthand. But instead it’s a heartfelt and jubilant love letter to a paradise found, lost, and reclaimed — Miami’s South Beach. It’s also the story of two friends who set out to document a slice of history — a portrait of the Jewish vacationers and retirees who migrated to Miami in the years after World War II to luxuriate on the beaches, at poolside and in the ballrooms of Art Deco hotels that lined the shore.

Andy Sweet and Gary Monroe photographed revelers who made the resort town their home in the winter months, as well as the year-round resident retirees who gravitated toward the sunny climes. Populated with many from the New York region from the city’s garment district or leather goods industry in the 1970s, the idyllic community was on its way out. Fueled by a sense of urgency was Sweet and Monroe’s dedication to recording the sun worshipers along the sandy coast. They set out to catch it on film before it faded away and was gone forever.

One of the more enigmatic parts of the story is Sweet, the curly-headed affable photographer. His color-saturated shots of Miami Beach denizens of the 1960s and ’70s captured the buoyant spirit of an era when South Beach was the shtetl by the sea — a place where The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel would surely have felt at home.

“…the story of two friends who set out to document a slice of history, the Jewish vacationers and retirees who migrated to Miami…”

Both Sweet and Monroe studied fine art photography in graduate and undergraduate school. Monroe’s lush, serene black and white images fit in with more traditional, formal art photography. Sweet’s work was of the on-the-fly aesthetic that seemed to say, shoot first and ask questions later — think Garry Winogrand. He was more interested in capturing the relationships among his subjects than properly framing his compositions. This hit-and-run sensibility speaks of the nervous energy exuded by a young man who truly enjoyed the company of the older folk with whom he endlessly chatted and recorded on film.

The film treats us to numerous shots taken by both photographers as well as home movie and newsreel footage, and it’s all a visual feast. It seems there was enough excitement on that strip of sand to keep their shutters clicking. In Miami’s heyday, Jackie Gleason taped his weekly TV show there, and Vegas entertainers, including the Rat Pack, Jerry Lewis, and Liberace graced the stages of the more posh resort hotels — the Fontainebleau being the crown jewel of the coast.

But the glitz of celebrities and cocktails by the pool was a temporary state of affairs in a city that was somewhat barren, humid and insect-infested before World War II. The advent of jet travel and air conditioning made the otherwise less than desirable location a must-see for Northern snowbirds. Miami’s golden age in the 1960s was followed by a downturn in the 1970s and ’80s. Rising rents began to price many of the working class inhabitants out of the market.

Adding to the problem was the Mariel Boatlift, a humanitarian effort that deposited numerous Cuban refugees onto the shores of Miami. While most were upstanding citizens, Castro saw the crisis as an opportunity to rid his island nation of hardened criminals populating Cuban prisons. Crime and violence rose dramatically, fueled by the burgeoning Colombian cocaine trade that ran rampant in the city. One news reporter commented that she covered 637 murders in one year in the 1980s. Paradise was well on its way to becoming the crime capital of the world.

“…digitally scanned and restored them and created new prints that burst with the vibrant colors…”

The remaining elderly population became more isolated and lonely as their living quarters deteriorated and friends died off. Many could no longer afford to live in a place that had once been their heart’s desire. Terrorized by crime in the streets and confined to their homes, especially after dark, the city had become a shell of its former self.

With a deteriorating city as a backdrop, the story took another tragic turn as Sweet met an untimely and violent end during the city’s most blood-soaked years. His friends and family remain heartbroken decades after the sudden and unexpected ordeal.

Thankfully, Sweet’s spirit and dogged dedication to his craft live on in his photos. His work might have vanished from the face of the earth as the South Beach community of years gone by had it not been for a surprising discovery, because the art storage facility that was holding his work lost the entire portfolio while transporting it to another building.

Miraculously, years later Sweet’s brother-in-law found the photographer’s decades-old contact sheets, which had been packed away and forgotten. He digitally scanned and restored them and created new prints that burst with the vibrant colors that were the photographer’s trademark. Because of this, Monroe, who continues to photograph Miami, was finally able to have a two-person exhibition with his and Sweet’s vintage photos.

Monroe’s later work focused on new immigrants arriving at the coastal city — Haitian immigrants, who have become a part of the modern community. It’s a fitting conclusion to an emotional story of a city and its culture that continue to grow and evolve.